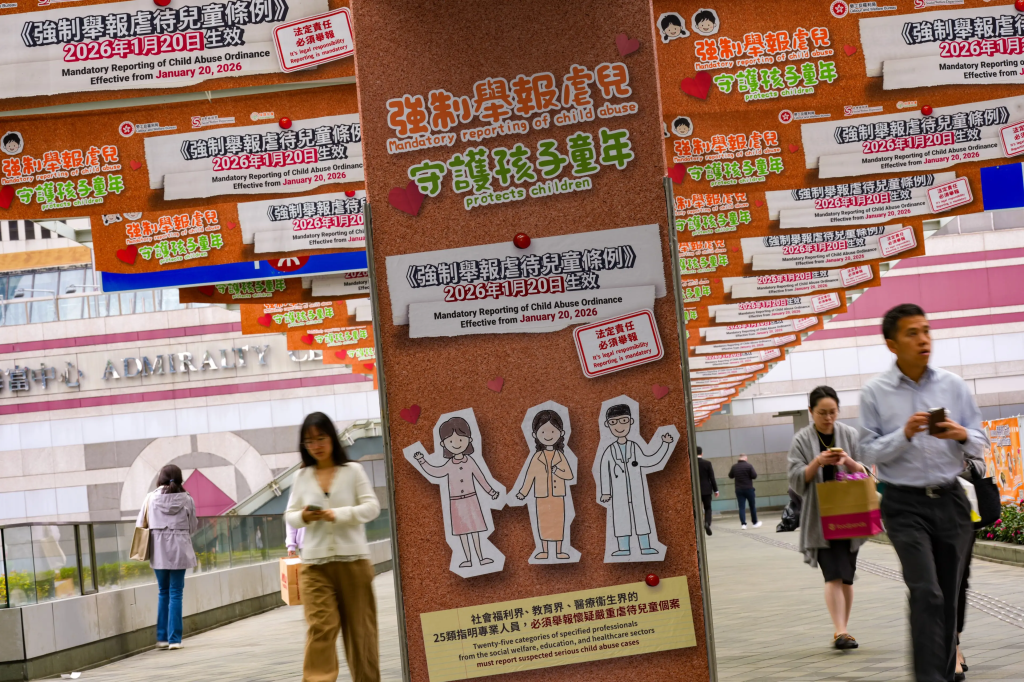

Hong Kong’s new Mandatory Reporting of Child Abuse Ordinance..

The Mandatory Reporting of Child Abuse Ordinance (Cap. 650) in Hong Kong:

A Child-Rights-Based Legal Analysis

1. Introduction

The Mandatory Reporting of Child Abuse Ordinance (Cap. 650), gazetted in July 2024 and entering into force on 20 January 2026, represents a significant shift in Hong Kong’s child-protection framework. By introducing a legal obligation for specified professionals to report suspected cases of serious child abuse, the Ordinance aims to strengthen early intervention and institutional accountability.

Mandatory reporting laws are not new in comparative legal systems. Many jurisdictions, including the United States, Australia, and parts of Europe, have long imposed legal duties on professionals to report suspected child abuse. However, such systems often raise complex legal, ethical, and human-rights concerns, particularly regarding privacy, professional autonomy, and the potential misuse of reporting mechanisms in family disputes.

This article examines the Ordinance from a child-rights and human-rights perspective, assessing both its protective potential and its legal risks.

2. Legal Background and Child-Protection Framework in Hong Kong

Hong Kong’s legal system is based on the common law tradition, with significant influence from English legal principles. Prior to the introduction of Cap. 650, child-protection obligations were largely governed by:

- Professional codes of conduct

- Administrative guidelines

- The Protection of Children and Juveniles Ordinance

- Family law principles prioritising the welfare of the child

However, the absence of a formal mandatory reporting regime created gaps in early detection. Professionals often relied on discretionary judgment, which sometimes resulted in delayed interventions or missed warning signs.

The new Ordinance seeks to address this structural weakness by converting professional expectations into binding legal duties.

3. Scope and Key Provisions of the Ordinance

The Ordinance imposes mandatory reporting obligations on twenty-five categories of specified professionals working in:

- Social welfare

- Education

- Healthcare

These professionals must report suspected serious child abuse where they have reasonable grounds to believe that a child is:

- Suffering serious harm, or

- At real risk of suffering serious harm

For the purposes of the law, a child is defined as any person under eighteen years of age.

This broad professional scope creates a multi-sectoral safety net, ensuring that children can be identified and protected across different institutional settings.

4. Criminal Liability and Enforcement Mechanisms

A defining feature of the Ordinance is the introduction of criminal sanctions for failure to report.

Professionals who fail to make a mandatory report may face:

- A Level 5 fine (currently HK$50,000), and/or

- Up to three months’ imprisonment

This provision reflects a clear policy decision to treat the failure to report suspected abuse not merely as professional misconduct, but as a criminal offence.

While this approach strengthens the seriousness of child-protection duties, it also raises questions about:

- Professional autonomy

- Defensive reporting

- The criminalisation of professional judgment

5. Safeguards and Exceptions within the Reporting Regime

To prevent excessive or inappropriate reporting, the Ordinance includes several statutory exceptions.

Under Section 4(2), reporting is not required where:

- The harm results solely from an accident

- The harm is self-inflicted

- The harm is caused by another child (excluding sexual conduct)

- The incident has already been reported

These safeguards serve an important balancing function. They recognise that not every injury or adverse event involving a child constitutes abuse.

From a legal perspective, these exceptions aim to ensure:

- Proportionality

- Legal certainty

- Protection against misuse of reporting obligations

6. Human-Rights Perspective and International Legal Standards

Mandatory reporting regimes must be assessed in light of international human-rights instruments, particularly:

- The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC)

- The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)

The Ordinance supports several key CRC principles, including:

- The best interests of the child (Article 3)

- The right to protection from abuse (Article 19)

However, mandatory reporting systems may also raise concerns under:

- The right to privacy

- Family autonomy

- Due process rights

If implemented without adequate safeguards, such regimes may result in:

- Unjustified state intervention in family life

- Over-reporting and institutional surveillance

- Disproportionate impact on vulnerable or marginalised families

7. Implications for Family Law and Custody Disputes

The Ordinance is likely to have significant practical effects in divorce and custody proceedings.

In contentious family disputes:

- Allegations of abuse may arise from emotional conflict

- Professionals may feel compelled to report defensively

- Reporting obligations may alter litigation strategies

While the law is designed to protect children, there is a risk that:

- Reporting mechanisms could be used strategically

- Investigations could intensify already fragile family dynamics

- Children could become instruments within parental conflicts

The safeguards in Section 4(2) attempt to mitigate these risks, but their effectiveness will depend on professional training and judicial interpretation.

8. Comparative Law Perspective

Mandatory reporting laws exist in many jurisdictions, but their design and impact vary significantly.

United States

Many states impose broad reporting duties, sometimes extending to all citizens. This has led to:

- High reporting rates

- Overburdened child-protection systems

- Concerns about unnecessary state intervention

Australia and Canada

These jurisdictions have more structured systems, combining:

- Mandatory reporting duties

- Professional training

- Integrated social services

Comparatively, Hong Kong’s Ordinance:

- Focuses on specified professionals

- Includes statutory safeguards

- Introduces moderate criminal penalties

This places it somewhere between strict punitive systems and balanced professional-duty models.

9. Societal and Institutional Impacts

The Ordinance is expected to reshape professional culture across key sectors.

Potential Positive Effects

- Earlier identification of abuse

- Stronger inter-agency coordination

- Increased accountability

Potential Risks

- Defensive or excessive reporting

- Increased state intrusion into family life

- Pressure on already stretched social services

- Distrust between families and professionals

The success of the Ordinance will depend heavily on:

- Training of frontline professionals

- Efficiency of child-protection services

- Judicial oversight

- Inter-agency cooperation

10. Conclusion and Recommendations

The Mandatory Reporting of Child Abuse Ordinance represents a major structural reform in Hong Kong’s child-protection system. By imposing legal duties on specified professionals, it seeks to close longstanding gaps in early detection and intervention.

However, mandatory reporting regimes are inherently complex. While they can enhance protection, they may also produce unintended consequences if implemented without careful safeguards.

Key Criticisms

- Potential criminalisation of professional judgment

- Risk of defensive or excessive reporting

- Possible misuse in custody disputes

- Concerns regarding privacy and family autonomy

Recommendations

- Provide comprehensive professional training on reporting thresholds

- Ensure proportional and child-centred enforcement

- Strengthen social-service capacity to handle increased reports

- Monitor the law’s impact on family-law disputes

- Establish independent oversight mechanisms

Final Remarks

The Ordinance reflects a commendable commitment to child protection. Yet its true success will depend not on the existence of reporting duties alone, but on how the system responds once a report is made. A balanced, rights-based implementation will be essential to ensure that the law protects children without undermining family integrity or professional judgment.

Footnote:

“The website https://www.childprotectiontraining.hk/home requires all children to complete an exam and obtain a digital certificate at the end of the training. Children are not allowed to continue with the training until they pass this exam and receive the certificate, making it functionally similar to a legal or mandatory requirement.”

Introduction: Burkina Faso’s New Law and Global Repercussions

As of September 1, 2025, Burkina Faso enacted amendments to the Family and Personal Status Code, which not only impact domestic law but also challenge the international community’s understanding of democracy, human rights, and the rule of law. The new legislation imposes 2–5 years of imprisonment and heavy fines for individuals who “promote homosexuality”; it provides for the deportation of foreign nationals engaging in such behavior and restricts adoption rights.

At first glance, the amendment may be justified as a measure to “protect societal values.” However, a deeper analysis reveals a punitive, exclusionary, and discriminatory approach that conflicts with fundamental principles of law. In particular, it contravenes the best interests of the child, the protection of family unity, equality, and privacy rights under both national and international standards.

The international community perceives Burkina Faso’s step as a new example of democratic regression in Africa, echoing similar legislation in Uganda, Nigeria, and Ghana, where such laws have historically increased violence, societal ostracization, and legal insecurity for LGBT+ individuals. By following a similar path, Burkina Faso risks not only its own citizens’ rights but also regional stability and the integrity of international human rights law.

This paper will provide a detailed analysis of the legal content of the law, its societal impact, and conflicts with international law, while critically examining how law can be misused to restrict individual freedoms under the guise of moral regulation.

Burkina Faso’s Legal System and Family Law Foundations

Burkina Faso’s legal system is historically rooted in French colonial law and continues to follow a civil law framework. While the Constitution guarantees fundamental rights and freedoms, in practice, political authority often instrumentalizes the law to achieve ideological goals.

Structure of Family Law

Family law in Burkina Faso is primarily designed to enforce “moral values”, rather than safeguard individual rights. In contrast, contemporary family law aims to protect privacy, equality, children’s best interests, and social diversity. Burkina Faso’s approach largely defines family solely through heterosexual marriage, marginalizing other identities.

Influence of Traditional Norms

Customary and religious norms significantly influence Burkina Faso’s legal culture. While modernization is claimed, in reality, laws often impose traditional values through state authority. The ambiguity of the “promotion of homosexuality” clause exemplifies this tension, violating the principle of legal predictability.

Critical Assessment

Rather than protecting individual rights, the new legislation transforms family law into a tool for exclusion. Restrictions on adoption jeopardize children’s right to a safe family environment, violating the principle of the best interests of the child. The legal system’s adoption of such an ambiguous, punitive, and discriminatory law highlights weak judicial independence and politicization of the law, with serious implications under international human rights norms.

Content of the New Law and Substantive Provisions

The September 1, 2025, amendment introduced three key provisions: criminal sanctions, deportation of foreigners, and restrictions on adoption.

“Promotion of Homosexuality” and Criminal Sanctions

The law criminalizes individuals who “promote homosexuality” with 2–5 years imprisonment and heavy fines. The vagueness of “promotion” undermines legal certainty. For example:

- A LGBT+ individual publicly expressing their identity could be prosecuted.

- Teachers educating against discrimination could face charges.

- Journalists reporting on LGBT+ rights could be penalized.

This ambiguity makes the law not only punitive but chilling, suppressing basic freedoms.

Deportation of Foreign Nationals

Foreigners engaging in “promotion of homosexuality” can be immediately deported. This poses a threat to international NGOs, human rights defenders, and even UN personnel operating in Burkina Faso. The law aims to shield the state from international oversight, serving isolationist and repressive purposes.

Restriction on Adoption

Adoption rights are denied to LGBT+ individuals or those deemed to “promote homosexuality,” undermining children’s right to a safe family environment. This contravenes the best interests of the child, as recognized by the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Critical Assessment

The law violates:

- Principle of legal certainty

- Proportionality

- The best interests of the child

- International cooperation and human rights norms

Thus, while appearing as a legitimate legal regulation, the law functions as a political instrument of repression, demonstrating how law can be misused to control ideological conformity rather than protect rights.

Child Rights and Adoption Implications

The law’s restriction on adoption is particularly contentious:

Violation of the Best Interests of the Child

The UN CRC Article 3 mandates that the best interests of the child must guide all actions concerning children. Burkina Faso prioritizes state ideology over children’s welfare, reducing them to objects of political control.

Restriction of Access to Family Environment

Children in need of adoption due to poverty, conflict, or family breakdown are denied access to loving homes. Restricting adoption based on sexual orientation undermines societal well-being and the future development of children.

Indirect Discrimination

CRC Article 2 prohibits discrimination. The law indirectly discriminates against children by limiting adoption opportunities for LGBT+ individuals, denying children rights based on adults’ identities.

Critical Assessment

The law creates double harm for children:

- Denial of safe family environments.

- Exposure to state-sanctioned ideological discrimination.

Thus, the law prioritizes ideology over children’s rights, conflicting with contemporary standards of child protection.

Human Rights Perspective: Conflicts with International Law

Burkina Faso’s law conflicts with several international human rights standards:

ICCPR

- Article 17: Right to privacy violated by criminalizing expression of sexual orientation.

- Article 19: Freedom of expression restricted.

- Article 26: Discrimination prohibited; law targets LGBT+ individuals.

African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights

The law undermines dignity, equality, and non-discrimination, violating the regional human rights framework.

UN CRC

Adoption restrictions violate Articles 3, 2, and 20, undermining child protection obligations.

European Court of Human Rights Precedents

Although not under ECHR jurisdiction, cases like Dudgeon v. UK (1981) and E.B. v. France (2008) highlight international standards protecting sexual orientation and adoption rights. Burkina Faso’s law is inconsistent with these principles.

Critical Assessment

The law represents a direct assault on universal human rights, prioritizing ideological conformity over legal protections. It isolates Burkina Faso from the international community and undermines its legitimacy under human rights law.

Societal Impacts

The September 1, 2025 amendment has profound societal implications:

1. Impact on LGBT+ Individuals

Although the law does not directly criminalize LGBT+ people, its broad “promotion of homosexuality” provision targets and marginalizes this group. Visibility is reduced, advocacy is stifled, and psychological pressure, social exclusion, and risk of violence increase.

2. Freedom of Expression and Organization

Civil society, academics, journalists, and human rights defenders may face charges if they publicly support LGBT+ rights. This seriously restricts freedom of expression and reduces civil society space.

3. Indirect Effects on Women and Children

The adoption restrictions negatively affect children seeking safe family environments. Moreover, gender equality initiatives are indirectly weakened, as discrimination based on sexual orientation is legitimized.

4. Social Polarization

By labeling certain groups as “undesirable,” the law fosters societal division. This may normalize discriminatory policies and weaken social cohesion.

5. Migration and Brain Drain Risks

Young and skilled individuals may seek opportunities abroad due to fear and lack of rights protections, potentially affecting Burkina Faso’s economic and social development.

International Reactions and Diplomatic Consequences

1. United Nations (UN) Reactions

The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights and special rapporteurs are likely to criticize the law, citing violations of freedom of expression and anti-discrimination principles. Burkina Faso will face scrutiny in UPR cycles.

2. African Union and Regional Reactions

The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights may intervene, as the law undermines regional human rights standards.

3. European Union and Western Countries

The EU and other Western nations could increase diplomatic pressure, possibly conditioning aid and partnerships on human rights compliance.

4. International NGOs

Human rights organizations such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch are expected to issue reports, damaging Burkina Faso’s international image.

5. Risk of Diplomatic Isolation

The law may strain relations with democracies that prioritize human rights, potentially affecting investment, international funding, and regional cooperation.

Comparative Perspective: Similar Laws in Other Countries

1. Uganda, Nigeria, and Ghana

- Similar laws exist criminalizing promotion of homosexuality or same-sex acts.

- Burkina Faso differs by broadly criminalizing expression and behavior, increasing arbitrariness.

2. Key Differences

- Other countries mostly criminalize sexual acts, while Burkina Faso targets speech, behavior, and adoption, making it more radical.

3. International Human Rights Perspective

Even in countries with similar laws, international criticism is widespread. Burkina Faso’s ambiguity and adoption restrictions intensify international scrutiny.

4. Critical Assessment

Compared to peers, Burkina Faso exhibits greater discrimination and legal uncertainty, subordinating individual and child rights to ideological goals.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Burkina Faso’s September 1, 2025 amendment violates both domestic and international human rights standards. Criminal sanctions, deportation, and adoption restrictions undermine basic freedoms.

Main Criticisms

- Legal vagueness and unpredictability (“promotion” concept)

- Violation of the child’s best interests

- Discrimination and human rights infringements

- Social and diplomatic risks

Recommendations

- Clarify the law to eliminate ambiguity and ensure proportionality

- Prioritize child welfare in adoption, removing ideological criteria

- Align domestic law with ICCPR, CRC, and the African Charter

- Promote social awareness and anti-discrimination education

- Engage civil society in protecting rights of LGBT+ individuals and children

Final Remarks

The law represents a regression in the rule of law and human rights, prioritizing ideology over rights and societal well-being. Reforming this law is essential to protect children, uphold equality, and maintain Burkina Faso’s standing in the international community.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Burkina Faso’s September 1, 2025 amendment to the Family and Personal Status Code raises serious concerns under both domestic law and international human rights law. The legislation, which imposes imprisonment and fines for individuals who “promote homosexuality,” allows for the deportation of foreigners and restricts adoption rights, thereby arbitrarily and discriminatorily limiting fundamental individual rights.

Key Criticisms

- Legal Uncertainty and Lack of Predictability: The concept of “promotion of homosexuality” is vague, undermining the principle of legal certainty.

- Violation of the Best Interests of the Child: Restrictions on adoption directly compromise children’s right to access a safe family environment.

- Discrimination and Human Rights Violations: The law conflicts with international treaties, including the ICCPR, CRC, and the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights.

- Societal and Diplomatic Risks: The law increases social exclusion, polarization, international isolation, and economic risk.

Recommendations

- Review and Clarify Ambiguous Provisions: The term “promotion” should be clearly and proportionally defined to prevent arbitrary interpretation.

- Prioritize Children’s Rights: Adoption processes must place the best interests of the child at the forefront, removing considerations of sexual orientation or ideological criteria.

- Align with International Human Rights Standards: Burkina Faso should implement reforms in compliance with ICCPR, CRC, and the African Charter.

- Promote Social Awareness and Education: Programs to prevent discrimination and increase societal awareness should be supported.

- Engage Civil Society: Barriers faced by NGOs working on LGBT+ rights and children’s rights should be removed, and freedom of expression safeguarded.

Conclusion

Burkina Faso’s legislative amendment presents serious risks to the impartiality of the law, the protection of human rights, and democratic standards. A critical review of this legislation is essential, not only to align domestic law with international norms but also to ensure the protection of individuals and the promotion of social peace. The reforms that Burkina Faso undertakes within this framework will be crucial for both domestic stability and its international reputation.

Denmark’s 2025 Immigration and Labor Policies: Current Regulations and European Implications

Introduction

I think Denmark’s immigration policies have undergone a remarkable transformation in recent years. Since the 2015-2016 migration crisis, European countries have adopted more cautious and controlled approaches to immigration. Denmark, in particular, has demonstrated this clearly through its center-left government. As of 2025, new regulations affect both labor migration and the movement of international students and asylum seekers.

In my opinion, the rationale behind these policies is twofold: economic considerations and the desire to maintain societal approval. I believe this strategy is likely to spark debates across Europe.

It seems necessary to understand that immigration policies cannot be confined to laws alone. Societal perception, economic balance, and international legal obligations must be considered together. In this article, I will analyze Denmark’s 2025 immigration policies under four main headings, adding my personal reflections, what I think should be done, and the potential impacts of these measures.

Labor Migration Regulations

I believe Denmark’s labor migration policies are among the most striking aspects of these reforms. As of July 1, 2025, the Positive List system has facilitated the entry of highly skilled workers. I think the update in salary thresholds, reducing the annual requirement from 514,000 DKK to 300,000 DKK, provides significant relief for both employers and migrants.

The Certified Employer (SIRI-approved employer) system allows selected employers to accelerate work permits for citizens from 16 designated countries. I think this is crucial because it addresses immediate labor shortages in key sectors such as healthcare, engineering, and IT. However, I also think restricting low-skilled labor may create workforce gaps in the long term.

It seems necessary that Denmark uses this system as a controlled and fair immigration management tool. In my opinion, continuous monitoring of compliance with EU standards and predicting potential labor market shortages are essential steps that should be taken.

Restrictions on International Students

I think this is perhaps the most controversial aspect of Denmark’s 2025 policies. From May 2025 onwards, international students from non-EU countries have faced severe restrictions: they are no longer eligible for work permits, post-graduation job-seeking visas, or family reunification if enrolled in non-full-time study programs.

I think these measures aim to prevent international students from exerting downward pressure on wages. However, it seems necessary that such regulations do not compromise the quality of education or the overall experience of students in Denmark. Otherwise, Danish universities could become less attractive in the long term.

Personally, I think Denmark’s strategy reflects a balance between economic logic and societal stability, but it must not lose sight of the human-centered perspective.

Asylum Policies and Deportation Practices

I think Denmark’s asylum policies in 2025 are among the most restrictive in Europe. In 2024, the number of approved asylum applications dropped to just 864 – the lowest in 40 years . This dramatic decline is not accidental; I believe it reflects a deliberate “zero refugee” approach by the Danish government.

It seems necessary to note that Denmark has introduced short-term protection programs and expanded deportation offices to manage the inflow of asylum seekers. From my perspective, these measures aim to control societal and economic impacts, but they also raise serious human rights concerns. I think the ethical implications of these policies are significant and cannot be ignored.

Personally, I think what should be done is a more balanced approach: Denmark needs to maintain border control and societal stability while also ensuring basic protections for vulnerable populations. Otherwise, the country risks international criticism and moral scrutiny, particularly from human rights organizations.

I also think it’s interesting that the government often justifies these policies in terms of economic efficiency and social cohesion. While this rationale may make sense from a pragmatic standpoint, I believe it’s crucial to consider long-term societal integration. Excluding refugees and limiting asylum may provide immediate relief to the labor market and social services, but it can create tensions and missed opportunities in the long run.

From my perspective, these policies illustrate a broader trend in Europe: countries are experimenting with extreme approaches to migration, which might serve as models but also as cautionary tales. I think Denmark’s approach will continue to spark debates both domestically and internationally.

International Cooperation and Legal Controversies

I think one of the most intriguing aspects of Denmark’s 2025 immigration policies is how they intersect with international law. Denmark has not acted in isolation; rather, it engages with Europe on migration debates, sometimes controversially. For example, together with Italy, Denmark joined eight other European countries in sending a joint letter urging a reinterpretation of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), arguing that the European Court of Human Rights limits national authority

I think this move is bold and reflects a broader tension: national sovereignty versus supranational obligations. In my opinion, it is necessary to carefully balance these interests. Denmark’s attempt to assert more control over its borders may make sense politically, but it risks friction with EU institutions and human rights bodies.

Another example that I think is worth noting is the postponement of the second round of parliamentary votes on citizenship legislation in 2025, now pushed to early 2026 .

I personally think this highlights how sensitive these issues are domestically. Delays and legal uncertainties affect both immigrants waiting for citizenship and the perception of Denmark in the international community.

From my perspective, Denmark’s approach shows that immigration policies cannot be purely domestic concerns. They inevitably interact with international law, European frameworks, and neighboring countries’ policies. I think what should be done is a more transparent dialogue between Denmark, the EU, and human rights institutions to ensure that restrictive policies do not inadvertently violate legal or ethical norms.

Overall, it seems necessary to recognize that while Denmark’s model may be pragmatic and politically appealing at home, it could create long-term diplomatic and legal challenges. I personally believe that other European countries will closely watch Denmark as a potential model, but they should also learn from its risks.

In my view, Denmark’s 2025 immigration and labor policies illustrate a highly strategic, yet controversial approach. By controlling labor migration through the Positive List and SIRI-certified employers, restricting international student rights, and adopting a “zero refugee” approach, the government clearly prioritizes economic stability and social cohesion. I think these measures are effective in the short term, but they also carry ethical, legal, and societal implications that cannot be ignored.

I personally believe that what should be done is a careful balance between pragmatism and human-centered policies. Denmark needs to manage immigration in a way that protects national interests while upholding basic human rights. The restrictions on students and asylum seekers, for instance, could be re-evaluated to ensure that Denmark remains an attractive and fair place for international talent and refugees.

It seems necessary to me that Denmark also engages more proactively with international and European institutions. Cooperation, dialogue, and transparency could help mitigate potential legal conflicts and enhance Denmark’s credibility on the global stage. In my opinion, ignoring international obligations or pushing too far could create long-term challenges that outweigh short-term gains.

Finally, I think Denmark’s model may serve as both a lesson and a warning for other European countries. While it demonstrates a firm, well-structured approach to controlling migration, it also raises critical questions: How far should a country go in prioritizing national interests over individual rights? How can Europe maintain unity while respecting national sovereignty? In my view, these are the questions we all need to reflect on as Europe faces ongoing migration challenges.

In conclusion, I believe Denmark’s 2025 policies are a bold experiment. They show that pragmatic migration management is possible, but I also think that without careful ethical and legal consideration, such policies may risk international criticism and domestic moral dilemmas. We should watch closely, reflect critically, and consider what lessons can be applied to other contexts in Europe and beyond.

Match-Fixing in Australian Football: A Sports Law Perspective

Recent match-fixing allegations in Australian football, particularly the “yellow card scandal,” have reignited debates surrounding sports law, encompassing disciplinary measures, criminal law, and international cooperation. This study examines the current legal framework in Australia, evaluates the potential benefits of the Macolin Convention, and offers a comparative analysis with Portugal and France. The paper highlights the challenges and opportunities for aligning Australian sports law with international standards.

Introduction

The integrity of sports competitions is a fundamental principle of sports law. Match-fixing represents one of the most severe threats to this integrity. The recent “yellow card scandal” in Australian football has drawn attention to both ethical and legal dimensions. Licensed betting operators reported unusual odds movements to law enforcement, demonstrating the role of private actors in maintaining public order. This case highlights the intersection between disciplinary law, criminal law, and international regulation.

Legal Dimensions of Match-Fixing

–Disciplinary Law

FIFA’s Disciplinary Code (Art. 18) and UEFA’s Code of Ethics (Art. 12) impose severe sanctions for manipulation of sporting competitions. The Australian Football Federation similarly enforces long-term bans on players who compromise match integrity.

–Criminal Law

Match-fixing extends beyond sports disciplinary mechanisms. Under Australian state laws, fraudulent activity and organized crime provisions may apply, creating an overlap between sports law and criminal law. Criminal prosecution may include imprisonment and financial penalties.

International Framework and the ”Macolin Convention”

The Council of Europe’s 2014 Convention on the Manipulation of Sports Competitions (Macolin Convention) mandates cooperation among states, sports organizations, and betting operators.

- Article 5: Obliges states to implement preventive measures.

- Article 11: Mandates international cooperation between law enforcement authorities.

Australia has not yet ratified the Macolin Convention. The absence of a uniform federal regulation leads to inconsistencies across states, weakening the effectiveness of anti-match-fixing measures.

Comparative Legal Analysis

- Portugal: Law No. 14/2024 prescribes up to eight years of imprisonment for match-fixing, alongside disqualification from sporting duties and ineligibility for public funding.

- France: Penal Code, Article 445-1-1, criminalizes manipulation of sporting events and imposes legal penalties.

These examples provide potential models for legislative reform in Australia.

Conclusion

The recent match-fixing allegations in Australian football underscore the multidimensional nature of sports law. Effective regulation requires:

- Comprehensive federal legislation,

- Ratification of the Macolin Convention,

- Coordinated efforts among sports federations, betting operators, and law enforcement.

Without such measures, match-fixing scandals will continue to undermine not only athletes’ careers but also public confidence in sports.

From a personal analytical perspective, the recent match-fixing allegations in Australian football illustrate not only the vulnerability of sports to manipulative practices but also the broader systemic challenges facing national and international sports governance. While disciplinary codes and criminal statutes provide a framework for punitive measures, the effectiveness of these instruments is contingent upon robust enforcement mechanisms and comprehensive regulatory alignment across jurisdictions. Australia’s current absence from the Macolin Convention exposes a significant gap in its capacity to engage in coordinated international action, leaving both athletes and federations susceptible to reputational and legal risks. Comparative examples from Portugal and France suggest that integrating criminal sanctions with administrative and sporting penalties can enhance deterrence; however, such measures must be accompanied by proactive education programs for athletes, transparent governance structures within federations, and real-time monitoring by betting regulators. Personally, I perceive this incident as a critical juncture that underscores the need for Australia to transition from reactive enforcement to a preventive, integrity-centered model. Only through embracing international best practices and cultivating a culture of accountability within all levels of sport can the country safeguard the legitimacy of its competitions and restore public confidence. Ultimately, the scandal demonstrates that sports law cannot exist in isolation: it must intersect strategically with ethics, governance, and criminal justice to effectively uphold the principles of fairness and integrity in contemporary sport.

References

- Council of Europe, Convention on the Manipulation of Sports Competitions (Macolin Convention), CETS No. 215, 2014.

- FIFA, FIFA Disciplinary Code, 2023.

- UEFA, UEFA Ethics and Disciplinary Regulations, 2022.

- Portugal, Law No. 14/2024 on Integrity in Sport, Diário da República, 19 January 2024.

- France, Penal Code, Article 445-1-1.

- Interpol & Europol, Match-Fixing Report, 2023.

- The Guardian, “The world betting game: is football more susceptible to match-fixing in Australia?”, 21 August 2025.

Highlights of International Legal Developments in the “Children’s Rights” section as of the first half of 2025

The year 2025 marked a period when children’s rights were re-discussed globally, risks shifted in magnitude with technological advancements, and states sought to respond more visibly and quickly at the legislative level. Across the world, many countries have proposed new legislation in areas such as child abuse, online safety, the right to education, the protection of refugee children, and child labor, implemented comprehensive reforms to existing regulations, or implemented special regulations on children’s rights for the first time. These developments were shaped not only by the legal framework but also by the impact of rising public awareness, international pressures, and the new threats posed by the digital world.

Redefining the Concept of Childhood

In recent years, the concept of childhood has evolved into a multidimensional phenomenon, not limited to biological age but shaped by developmental, psychosocial, digital, and cultural layers. This situation, particularly with the increased digitalization following the pandemic, is bringing children online at an earlier age, presenting both opportunities and threats.

In 2025, many countries adopted new regulations that included children’s digital rights, recognizing the need to redefine the concept of “childhood” in line with the times and technology. This transformation has come to be viewed not only as a pedagogical issue but also as a legal and ethical one.

Driving Forces of Legal Developments

Four fundamental dynamics appear to be driving legal developments in the field of children’s rights:

The Impact of International Conventions: Documents such as the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), the Lanzarote Convention, and ILO Conventions Nos. 138 and 182 were shaping the domestic laws of many countries in 2025.

Technological Threats: Problems in areas such as cyberbullying, online abuse, and AI-assisted content filtering forced countries to develop new legal mechanisms. Liability regulations for social media companies were particularly noteworthy.

Social Pressure and Awareness: Public pressure forced some countries to amend their laws due to women’s and children’s rights activism, media campaigns, and civil society organizations.

The Refugee Problem Evolving into a Crisis: Regulations regarding the protection of children displaced by reasons such as war, climate change, and migration occupied a prominent place on the legal agenda for 2025.

Expansion of Protective Law

Child protection legislation, which in the past primarily focused on physical violence and the right to education, evolved into a more complex and multilayered structure in 2025. The boundaries of protective law have been expanded in the following areas:

Online privacy and data security

Making psychological violence within the family visible

Equality and combating discrimination in the school environment

Freedom of expression and the right to self-actualization

The effects of climate change on children

In addition, some countries have taken steps to directly provide constitutional protection to children.

Preventive and Restorative Legal Approaches

Another prominent theme in 2025 is the development of preventive and restorative justice models, not solely based on punitive sanctions. For example, practices such as blocking harmful content from children on social media platforms through automatic filtering systems before it’s even published; providing digital literacy training to parents; providing psychosocial support to child victims; and designing restorative justice processes between the perpetrator and the victim have brought about legal steps aimed not only at punishment but also rehabilitation.

So…let’s move on to examining the countries that “have attempted and/or implemented significant legislative amendments in the field of children’s rights; or have existing legislative proposals,” specifically for the first half of 2025, the objectives these countries sought when introducing regulations, and the texts of these amendments.

USA..

The “Kids Online Safety Act,” which improves children’s online privacy, has been introduced to the Senate.

According to the bill, there is a distinction between “Child” and “Minor” as follows:

The term “Child” means any individual under the age of 13.

The term “Minor” means any individual under the age of 17.

Each digital platform covered by the bill shall exercise reasonable care in the creation and implementation of any design feature to prevent and reduce the following harms to minors, if a reasonable and prudent person would consider such harms to be reasonably foreseeable by the covered platform and that the design feature is a contributing factor to such harms:

(1) Eating disorders, substance use disorders, and suicidal behaviors.

(2) Depressive disorders and anxiety disorders, if such conditions have objectively verifiable and clinically diagnosable symptoms and are associated with compulsive use.

(3) Patterns of use that indicate compulsive use.

(4) Physical violence or online harassment that is severe, pervasive, or objectively offensive enough to interfere with a significant life activity of a minor.

(5) Sexual exploitation and abuse of minors.

(6) Distribution, sale, or use of narcotics, tobacco products, cannabis products, gambling, or alcohol.

(7) Financial damages resulting from unfair or deceptive acts or practices (as defined in the relevant section of the Federal Trade Commission Act).

The bill also comprehensively addresses platforms’ duty of care, the requirement to implement protective measures, particularly for minors, transparency in these actions, and the imposition of administrative fines upon inspection if they fail to do so. Technical penalties, such as the closure of the relevant platform in the event of recurrence, age verification, and reporting processes are also discussed.

The bill also establishes a “Children’s Online Safety Council.”

Accordingly, the Council’s duties are to submit reports to Congress containing recommendations and suggestions on matters related to the online safety of minors. The Council will address the following topics:

(1) Identify emerging or existing risks of harm to minors associated with online platforms;

(2) Recommend measures and methods for assessing, preventing, and mitigating harms suffered by minors online;

(3) Recommend methods and themes for conducting research on online harms to minors, including in English and non-English languages; and

(4) Recommend best practices and clear, consensus-based technical standards for transparency reports and audits, as required under this heading, including methods, criteria, and scope to promote overall accountability.

Continuing with the United Kingdom.

The “Online Safety Act” has come into effect, making age verification mandatory on social media.

The online age verification law, which aims to protect children from harmful content in the UK, officially came into effect on July 26. The law mandates digital platforms, particularly pornography sites, to verify the age of their users. Approximately 6,000 pornography sites have announced that they have become compliant with the law and implemented age verification.

The law isn’t limited to adult content platforms. Social media and dating apps like Xbox, Reddit, Bluesky, X, and Spotify are now also requiring their UK users to prove their age through selfies, passports, or government-issued ID documents. This is being interpreted as the beginning of a new era in internet use:

“Is this the end of an anonymous online existence?”

However, despite their stated aim to protect children, these apps have drawn harsh criticism from privacy advocates. Digital rights organizations like the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) warn that age verification systems can compromise user privacy and eliminate anonymity. Indeed, a recent example confirms these concerns. Selfies and digital ID documents collected by the dating app Tea for its age verification process were exposed on cyber forums in a data leak. This incident exposed the vulnerability of security systems.

Users have already begun developing various methods to bypass the new age verification requirements. Creating fake ID documents, creating fake selfies using video game characters’ faces, or bypassing geographic restrictions via VPN are among the most common “digital escapes,” but these seemingly creative solutions also carry serious risks. Using fake documents is a crime that can result in legal penalties, while sharing these documents on platforms vulnerable to fraud can expose users to threats such as identity theft and data leaks.

In other words, those who try to trick systems are often forced to compromise their own security.

While this step taken by the UK is designed to ensure children’s safer online behavior, it could pave the way for “age verification” to become the new digital standard around the world. Similar discussions, particularly in European Union countries and the United States, indicate that the anonymous nature of the internet is increasingly being regulated.

This brings to mind a digital world in which users may be forced to reveal their identities not only when producing content but also when consuming it.

All these developments bring us to the heart of a fundamental dilemma at the heart of the digital age:

“Protecting children online or defending individuals’ right to privacy?”

This dilemma creates a deep fault line not only technologically but also in its ethical, legal, and societal dimensions. On one side, there are lawmakers and families trying to prevent harmful content to which children are exposed; on the other, there are digital rights organizations, activists, and other dissident individuals who advocate for a free and anonymous internet. With the increasing prevalence of artificial intelligence, facial recognition technologies, and biometric data, the boundaries of privacy are being redrawn daily.

In conclusion, the UK’s online age verification initiative should be considered not just a law, but a turning point that will influence the trajectory of the digital age.

How this process is managed, the extent to which states will respect individual rights, and how technology companies will protect user data will determine the boundaries of the future internet. Perhaps most importantly, users must no longer be merely content creators but also the greatest defenders of their digital rights.

Now, let’s move on to Australia.

Legislative proposals have been prepared to ban social media use under the age of 16.

A social media ban targeting children under the age of 16 has been passed by the Australian Parliament, a world first.

The legislation would fine platforms like TikTok, Facebook, Snapchat, Reddit, X, and Instagram up to 50 million Australian dollars ($33 million) for their systematic failure to prevent children under 16 from having accounts.

The Senate passed the bill by 34 votes to 19. The House of Representatives overwhelmingly approved the bill by 102 votes to 13.

The House of Representatives passed the Senate’s opposition amendments, effectively signing the bill into law.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese said the legislation supports parents concerned about online harm to their children.

Now we look at Canada.

Parliament passed education reform to protect the cultural identity of Indigenous children.

Germany…

Germany does not want to ban social media for children under 16, citing the right of children and young people to participate digitally and explore their digital lives safely.

However, in the country, parental consent is required for children under 16 to use social media. It appears that there is no rigorous verification of whether this consent has actually been given by parents. Children may provide false birth information when registering on social media platforms.

This situation often doesn’t result in sanctions against social media providers. Germany places the responsibility for age limit checks on social media companies.

The German Ministry of Family, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth points out that the European General Data Protection Regulation (DSGVO) requires consent from parents of children and adolescents under the age of 16 for the processing of personal data by service providers.

Italy..

New legislation has been adopted to combat bullying and abuse in schools.

The law instructs the government to establish a technical committee for the prevention of bullying and cyberbullying within the Ministry of National Education, comprised of experts in psychology, pedagogy, and social communication.

Furthermore, the government will conduct periodic information campaigns on the prevention and awareness of bullying and cyberbullying, as well as parental control techniques.

The government is also instructed to adopt one or more legislative decrees within 12 months establishing other appropriate measures to assist victims of bullying and cyberbullying, including the 114 public emergency number for Childhood Trauma, which is accessible free of charge and 24/7.

This public number will be tasked with providing psychological and legal assistance to victims, their families, and friends, and, in the most serious cases, immediately report dangerous situations to the police.

Furthermore, the National Institute of Statistics will be required to conduct a survey every two years to measure the problem of bullying and cyberbullying and identify those most exposed to these risks.

Under the new legislation, each school: It must adopt an internal regulation on the prevention of bullying and cyberbullying and establish a permanent supervisory board composed of students, teachers, families and experts.

The law designates January 20th as “Respect Day” each year to examine the issue of respect for others, raise awareness about psychological and physical non-violence, and combat all forms of discrimination and abuse.

We’re moving on to Spain.

The draft law, designed to protect children in digital environments, was approved by the Council of Ministers in March 2025. It includes measures such as raising the age for opening a social media account from 14 to 16, requiring default parental control systems on devices, and defining crimes related to AI-based child pornography and deepfake content.

ICT product manufacturers are now required to offer free parental control systems activated at the time of purchase.

The regulation prohibits in-game random reward mechanisms, such as Lootbox, that interact with children for those under the age of 18.

The new regulation also introduces provisions penalizing online grooming or the creation of criminal profiles, as well as virtual remote access bans.

Portugal..

A law introducing harsh penalties to combat child labor has entered into force.

The political party Bloco de Esquerda (BE) is proposing raising the working age from 16 to 18 in Portugal to align it with the duration of compulsory education. This step aims to prevent children from entering the workforce before completing their education.

The proposal has been debated in parliament and discussed in committees, but has not yet been enacted.

Unfortunately, the majority appears to be cautious about this proposal; some parties argue that this change could alienate young workers from the formal system and make it more difficult to monitor them.

We continue with Sweden.

New regulations have been made to the Parental Code.

The amendments, which came into effect on January 1, 2025, define children’s rights regarding custody, residence, and visitation (boende och umgänge). These rules are now in effect for all ongoing cases.

The principle of “best interests of the child” (barnets bästa) is taken into account when making decisions to ensure the safety and well-being of children.

Furthermore, a new Social Services Law proposal was adopted on January 23, scheduled to come into force on July 1, 2025.

The new Social Services Law strengthens children’s rights by aligning it with the Convention on the Rights of the Child. The law states that “social services must take the child’s views into account when assessing the child’s best interests.” Children also have the right to information about their interventions, and social services must ensure that the child understands this information.

The new bill includes the following:

Social services should be more preventative and identify needs before they become too serious;

Social services’ preventative work against crime should be clarified;

It should be easier to access social services and receive help when needed; and

Social services should be able to respond more quickly in emergencies.

Again;

A bill has been introduced that will enable the monitoring of electronic communications of children under the age of 5, with a proposed wiretapping authorization.

Ju2024/02286 – Data lagring och åtkomst till elektronisk information (Regulation on the storage of electronic communication data and access to law enforcement authorities)

Children’s rights organizations in the country oppose this proposal as an invasion of children’s privacy and call for respect for legal rights.

Let’s look at Norway.

Increased oversight of social media platforms has been implemented to address children’s digital rights.

Furthermore,

The Norwegian government is taking decisive action to protect children online by proposing a public consultation on a new law that would ban social media platforms from providing services to children under the age of 15.

Recognizing the serious impact of screen use and social media on children’s sleep, mental health, learning, and concentration, Norway appears committed to creating a safer online environment for children.

Prime Minister Jonas Gahr Støre said, “This is one of the most pressing social and cultural challenges of our time and cannot be solved by national measures alone. We aim to strengthen cooperation with Europe to ensure a safe digital environment for children and young people.”

Minister of Children and Families Lene Vågslid said: “We cannot allow screens and algorithms to take over childhood. Children must be protected from harmful content, abuse, commercial exploitation, and misuse of their personal data,” she said.

Developing effective enforcement mechanisms for absolute age limits is both a legal and technological challenge. Currently, there is no fully effective solution for age verification. Norway aims to work closely with the EU and other European countries addressing the same issue to develop practical and accessible solutions.

Karianne Tung, Minister of Digitalization and Public Administration, said:

“Digitalization transcends national borders.

Norway is working closely with the EU on how to regulate large technology companies. We want to find common solutions on age verification and age restrictions.”

The proposed law aims to protect children and young people from potential harms associated with social media use, including exposure to criminal activity.

The law also includes a definition of what constitutes a social media platform, which will play a key role in determining which services are subject to age restrictions.

Most importantly, the law will not restrict children’s participation in leisure activities or social communities. The law is designed to respect children’s fundamental rights, such as freedom of expression, access to information, and the right to association.

Exceptions will be proposed for services such as video games and platforms used for communication purposes related to school or extracurricular activities.

The Norwegian government is also implementing several complementary initiatives to protect children online:

Increasing the age of consent under the GDPR for the processing of personal data by information society services to 15 years.

Publishing recommendations from national health authorities on screen use, screen time, and social media.

Removing mobile phones from schools, with a clear national proposal.

Proposed legislation to increase penalties for violations of child-targeted marketing regulations.

Combating online crime and exploitation of children and young people. Various issues, such as:

In Norway:

72% of children aged 9-12 use social media.

75% of the population supports electronic age verification on social media.

60% believe that age limits for social media use should be imposed by the government, not platforms or parents.

Denmark…

A new national strategy plan for children’s internet safety has been implemented.

Under the EU Digital Services Act (DSA), Denmark has launched a pilot program for an age verification app for children’s internet safety. This app will be used to verify those over the age of 18, ensuring the protection of personal information.

The Danish government has effectively implemented the DSA to tighten control over issues such as cyberbullying and harmful content, which can lead to addiction on online platforms.

The government aims to make age verification tools mandatory to protect children online.

Following a proposal from the Danish Welfare Commission, children aged 7–16 are prohibited from bringing mobile phones to school; this practice is being made legal in all folkeskolle (primary and secondary schools).

It is also recommended that children under the age of 13 not be given smartphones or tablets.

Sikker Internet Centre Danmark (Danish Safer Internet Centre) provides awareness raising, a helpline, and psychosocial counseling to ensure a safe online experience that respects children’s digital rights.

This structure operates within the BIK+ platform, a joint initiative of the EU.

As part of “Sikker Internet Day” (Safer Internet Day) for 2025, a conference focusing on children’s digital rights was held in Copenhagen on February 26.

Belgium..

As part of the joint Child-Friendly Justice Project of the Council of Europe and the EU, Belgium launched its new “Child-Friendly Justice Assessment Tool” in June 2025. This tool aims to align the justice system with child-focused norms, with Belgium participating as a pilot country in this process.

The Council of Europe’s Children’s Rights Division, together with representatives of Belgium, Poland, and Slovenia, presented this vital new document at a high-level meeting held in Brussels during the Polish Presidency of the Council of the European Union.

This innovative tool, a product of the Joint European Union/Council of Europe Project on Child-Friendly Justice (CFJ Project), is designed to enable member states to rigorously assess and subsequently strengthen their national justice frameworks. By providing clear indicators, it enables a comprehensive assessment of legislation, institutions, and practices, ensuring their compliance with the Council of Europe’s established Child-Friendly Justice Guidelines.

Following a practical demonstration of the Assessment Tool, compelling presentations were made from Belgium, Poland, and Slovenia, the key focus countries of the CFJ Project. The common findings from country-specific self-assessments highlighted the practical value of such tools in promoting progress and mutual learning across the continent.

This new Assessment Tool is envisioned as an important reference for national authorities and all professionals interacting with children within the legal system. It will facilitate the identification of strengths, the addressing of shortcomings, and the long-term monitoring of progress, ultimately contributing to broader European efforts to protect children’s rights in all proceedings affecting children.

The tool is currently available in English, with translations into French, Dutch, Polish, and Slovenian underway, and its official release is expected in the second half of 2025.

Poland

A bill imposing new duties on electronic service providers to limit children’s access to harmful content (including pornography) online was submitted to public consultation in February 2025.

The bill:

Requires providers to conduct risk analyses,

Establishing age verification mechanisms before pornographic content is displayed,

Creating a domain name blocking system to prevent undesirable user experiences.

It proposes the development of independent systems that do not rely on direct biometric verification or user testimony.

Penalties are quite severe; platforms and internet service providers that fail to provide verification may be subject to administrative fines of up to PLN 1 million (approximately EUR 230,000).

Czechia

With a bill passed in 2025, the Czech Republic allows children under 14 to work during summer vacation under certain conditions. This regulation recognizes the right of some children to work while also introducing strict controls and restrictions to protect their education and health. However, this amendment is not seen as part of a broader strategy to combat child labour, as it has been prepared with a rather narrow and shallow perspective.

Consider Hungary.

On March 18, 2025, the Hungarian Parliament passed a law further strengthening the “Child Protection Act.” This law prohibits events involving “gender reassignment or homosexuality” for children. It also introduced a regulation allowing the use of facial recognition technology to identify participants in such events.

On April 14, 2025, the 15th amendment to the Hungarian Constitution was adopted. This amendment controversially defined “person” as “male or female” in Article L(1) of the Constitution and guaranteed the right of every child to “the protection and care of their physical, psychological, and moral development” in Article XVI(1).

We look at Ukraine, a country victimized by war.

Ukraine has launched various projects for the protection and rehabilitation of child victims of war within the framework of the Council of Europe’s Children’s Rights Strategy for the period 2022-2027. These projects aim to protect children from violence, enhance their access to fair judicial processes, and strengthen psychosocial support services. Efforts to protect displaced, parentless, or victims of violence are particularly prominent.

During the Russian occupation, Ukraine faced serious human rights violations, including the forced deportation of children and their military training in Russia. International organizations and the Ukrainian government emphasize that these violations should be considered war crimes. The European Parliament adopted a resolution on this issue, stating that the forced deportation and military training of children are against international law.

UNICEF and the United Nations are running various rehabilitation programs for child victims of war in Ukraine. These programs aim to ensure that children receive psychological support, continue their education, and grow up in safe environments. In particular, efforts are being made to prevent and treat injuries resulting from mines and unexploded ordnance.

We’re coming to South Africa…

Regulations have been introduced to ban child marriage.

The bill proposes to completely ban child marriage in both civil and traditional marriages, limiting the marriage age to 18. In this context:

Marriage with individuals under the age of 18 will be strictly prohibited; under current law, 12-year-old girls and 14-year-old boys could be married, though unfortunately not acceptable, with parental or local court permission.

The bill subjects individuals who carry out or facilitate child marriage to criminal sanctions: imprisonment or a fine could be imposed.

During the bill’s approval process, campaigns and public hearings were held, and many citizens and NGOs: He argued that the marriage age should be lowered from 18 to 21. Let’s look at Nigeria…

The Federal Government has decided to review the National Policy and the 2021–2025 National Child Labour Elimination Action Plan in collaboration with the ILO.

As part of the policy review, the hazardous work list will be updated and existing legal gaps will be addressed.

On February 14, 2025, the Federal Ministry of Labour and Employment, the ILO, and the National Child Labour Elimination Steering Committee launched a new platform and mobile application.

This tool is used for centralized reporting, monitoring, and rapid response to child labour cases.

Nigeria has also incorporated ILO Conventions No. 137 on the Minimum Age for Employment and No. 182 on the Prohibition of the Employment of Bad Forms into its domestic law.

Egypt

A new budget increase and legal amendments have been made to ensure children’s right to education.

The Egyptian Government approved the budget for the 2025/26 fiscal year, which begins in July 2025; The total borrowing target was set at 4.6 trillion Egyptian pounds (~91 billion USD).

Total spending increased by 18%, and the share allocated to education also increased compared to previous years. There was a significant expansion in resources allocated to areas such as social services, education, and healthcare.

Despite this, this budget still falls short of the constitutional requirement to allocate at least 4% of GDP to preschool and primary education, with only approximately 1.7% of government spending allocated to education.

Kenya..

As of April 29, 2025, the Communications Authority of Kenya (CA) published a Child Online Protection and Security Industry Guide covering the entire IT sector.

The guide aims to protect children under 18 from online risks by:

*Age verification systems, parental controls, default privacy settings,

*Complaint and reporting mechanisms, privacy-by-design practices,

*Requiring suppliers and content providers to establish child safety policies.

The Free Pentecostal Fellowship of Kenya has launched a mobile application called the Linda Mtoto Early Warning System in the Busia region.

The system allows users to anonymously report child abuse, exploitation, or neglect via SMS.

Case reports are reported to local authorities; the system will be operational in a modular manner in the Teso North, Teso Central, and Busia regions in 2025.

Moving back to the Americas…

Brazil…

CONANDA Resolution No. 245, dated April 5, 2024, established key principles governing the rights and privacy of children and adolescents in the digital world.

The decision includes:

Only necessary data must be collected,

Clear and understandable information must be provided,

The basis for consent must be free, informed, and clearly stated,

Age verification systems must be made mandatory,

Digital platforms must be accountable and publish annual risk reports.

The ANPD has prioritized child data protection as part of its 2025 Regulatory Agenda.

Among the agenda targets are:

Age verification,

Parental consent mechanisms,

Implementation of privacy-by-design policies,

Regulation of biometric data, and the mandatory use of risk assessment reports (PIA).

The ANPD is developing specific guidelines on child data protection, particularly regarding the use of facial recognition systems, educational platforms, and artificial intelligence.

We examine Argentina.

It became the first Latin American country to impose age restrictions for children’s social media use.

Chile.

A national prosecutor’s office for children’s rights violations has been established.

The “Brigada Investigadora de Delitos Sexuales y Menores” (BRISEXME), under the Jefatura Nacional de delitos contra la Familia (JENAFAM), is a special police unit responsible for conducting investigations and prosecutions related to crimes against children.

According to the Penal Code enacted in 2019 (Article 94 bis), the statute of limitations for sexual crimes against children has been abolished; thus, prosecutors can intervene in these cases indefinitely.

Looking at Colombia:

Rehabilitation programs to reduce the impact of war on children have become legal.

Ley 2421 de 2024, which entered into force on August 24, 2024, strengthens Ley 1448 de 2011 (Law on Victims and Land Restitution), particularly with respect to child victimization.

Under this law:

The state is obligated to develop a psychosocial and health rehabilitation policy for children and youth. Programs supported by trained personnel ensure the reintegration of victims into society and their psychological recovery.

Special support and resources are allocated specifically for children who have been abused, exploited by armed groups, or victims of conflict.

Rehabilitation and psychosocial support for children in Colombia are legally guaranteed.

Ley 2421, through 2024, defines the development of public policies, allocation of financial resources, and coordination mechanisms specifically for child victims. This implementation is carried out by institutions such as the ICBF and the UAEARIV, and aims to support child victims in terms of health, education, family unity, and rights.

Mexico…

In 2025, the Supreme Court of Mexico (SCJN) ruled that child sex crimes would no longer be subject to a statute of limitations in criminal and civil cases. This decision aims to provide victims with more time to heal from their trauma and ensure justice.

Amendments to the Federal Penal Code have increased penalties for child sexual assault. For example, the penalty for pederasty has been increased from 17 to 24 years. These reforms aim to impose harsher sentences on offenders and protect victims.

In the State of Yucatán, amendments to the Penal Code in 2025 increased penalties for child sexual assault. These changes strengthen local efforts to protect children.

In Mexico, to prevent child sexual abuse in the digital environment, criminal sanctions have been introduced against individuals who engage in sexual abuse with children through social media. This measure aims to increase child safety in the digital environment.

Various laws and protocols are in place to protect the rights of child victims and provide them with psychosocial support. For example, the “Protocol for the Prevention of Sexual Abuse of Children” (Protocolo de Prevención del Abuso Sexual a Niñas, Niños y Adolescentes) provides a framework for the protection and support of victims.

Japan…

Age verification systems have been made mandatory for children’s online safety.

Japan has implemented various regulations to ensure the safety of children on social media platforms. For example, Instagram launched “Teen Accounts” in January 2025 for users aged 13-17. These accounts only allow messaging with approved followers, and users under 16 require parental consent to change security settings.

Additionally, online service providers in Japan are required to use digital identity verification systems to verify users’ ages. These systems use various methods to verify users’ identities.

Japan is working to strengthen its digital identity verification systems. For example, “My Number” cards are used to verify individuals’ identities and are equipped with IC chips to enhance security in online transactions. Such digital identity verification systems are expected to support age verification processes on online platforms.

South Korea

South Korea has taken a significant step toward protecting children in the digital environment, establishing the Digital Children’s Rights Commission. This commission works to ensure children’s online safety, protect their digital rights, and mitigate the risks they face in the digital world. The commission aims to safeguard children’s digital rights by working in collaboration with government agencies, civil society organizations, and other stakeholders.

This step has become a global priority for children’s rights due to the rapid development of the digital world and the increasing potential risks children face in this environment. The United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child has issued recommendations to protect children’s rights in the digital world and urged states to take measures. In this context, South Korea’s establishment of the Digital Children’s Rights Commission aims to ensure children have a safer presence in the digital environment by demonstrating an approach consistent with international standards.

The Commission’s activities include developing various strategies to reduce the risks children face in the digital world, increase their digital literacy, and protect their digital rights. These efforts demonstrate South Korea’s commitment to protecting children’s safety and rights in the digital world.

Let’s also take a look at China:

China has taken significant steps toward integrating digitalization into its education system by 2025. In particular, Beijing has made artificial intelligence training mandatory for all students from primary to secondary school. As part of this initiative, students will receive at least eight hours of AI training annually. The training is differentiated by age group:

Primary school students: Basic AI concepts and applications.

Middle school students: Use of AI in daily life and schoolwork.

High school students: In-depth studies on AI applications and innovation.

This reform aims to increase China’s competitiveness in the global AI race.

China has introduced strict regulations to prevent children’s addiction to digital games. Specifically, during the 2025 winter break, children’s total gaming time has been limited to 15 hours. This is a measure aimed at reducing children’s gaming addiction and promoting a more balanced lifestyle.

Additionally, regulations implemented in 2021 limited the gaming time of individuals under the age of 18 to three hours per week. These regulations require gaming companies to use authentic identity verification systems and not provide services outside of designated hours.

India, another country with a very high population density,

India has introduced new penalties for child labor. In India, under the Child and Adolescent Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act of 1986, the employment of children under the age of 14 is prohibited. Adolescents between the ages of 14 and 18 are permitted to be employed only in non-hazardous work. As of 2025, penalties for employers who violate this law have been increased: Child Labour: Imprisonment from 6 months to 2 years and a fine of 20,000 to 50,000 INR. Repeat offenders: Up to 3 years in prison and a fine of up to INR 1,000,000. These penalties have been further tightened by reforms, particularly in the state of Gujarat. Various measures are being implemented across India to combat child labor:

Gujarat State: Between 2020 and 2025, 4,824 raids were conducted, and 616 child laborers were rescued. These operations resulted in 791 criminal cases and 339 criminal complaints.

Bihar State: As of 2025, 30 children were rescued, each receiving financial support of 25,000 Indian Rupees. An additional contribution of 5,000 Indian Rupees was also made for each rescued child.

Such practices are implemented to ensure children’s right to education and provide economic support to families.

Pakistan..

In 2025, Pakistan took a significant step by enacting a law in the capital, Islamabad, banning child marriage. This law set the minimum age for marriage for both girls and boys at 18, criminalizing child marriage. The law also repealed the old 1929 law regulating child marriage.

⚖️ Key Articles of the New Law

Marriage Age: The marriage age for both girls and boys has been set at 18.

Punishment Sanctions: Those who facilitate, force, or organize child marriage will face prison sentences of up to 7 years and a fine.

Courts: Cases related to child marriage will be heard only in regional and high criminal courts.

Protection Measures: The law includes measures such as confidentiality and anonymity to protect victims.